Rethinking architectural ethics amid death and climate collapse

Architecture & Activisme

Amidst professional insecurity, educational denial, and the monetization of climate disaster, this text calls for a rethinking of our practices: building less, in order to learn to deal with extinction and the finitude of life.

➔ Auf Deutsch : Architektur und die berufliche Ironie des Klimakollapses

➔ En français : Repenser l'éthique du projet architectural à l’ère de la mort et l'effondrement climatique

➔ In Italiano : Ripensare l'etica del progetto architettonico nell'era climatica

As the climate crisis intensifies, the architectural profession faces a profound paradigm shift: from designing for permanence to confronting impermanence.

Traditionally tasked with creating variations on ‘shelter’, with a handful of the more ethically inclined seeking to address the right to refuge and how to enable community resilience, architects are increasingly compelled to anticipate disaster, displacement, and death. This emergent practice—what may be termed death architecture—highlights a vocational paradox: a discipline trained to sustain life now grapples with the aesthetics and logistics of its cessation.[1] From fire-resistant shelters and flood memorials to climate-adaptive cemeteries and extinction archives, the built environment is being reimagined as a site of mourning, memory, and managed collapse.[2]

This shift coincides with a broader economic precarity within the profession. Many architectural workers already experience underemployment, exploitative compensation, or chronic instability. Only a small minority—approximately 10%—earn more than $22 per hour, a wage that lags behind those of medical receptionists, warehouse workers, and plumbers.[3] In this context, the so-called ‘new market opportunities’ arising from climate collapse offer a grimly ironic form of professional relevance—one rooted not in hope or growth, where architects may gain work and recognition by creating spaces for thriving communities and aspirational futures, but instead by responding to disaster, managing decline, and commemorating what has been lost.

Death as a civic necessity

Preparing for death as a civic necessity, which in essence involves deliberately incorporating preparation for death and mortality into urban planning and architectural practices, treating it as an essential civic function rather than an aberration or afterthought, offers a critical and often overlooked lesson in architectural pedagogy and professional practice. While the global North still has the privilege to incorporate death-responsive design proactively, as a matter of civic foresight, communities in the global South have been forced by necessity to develop these approaches reactively. For instance, during a severe heat wave in Karachi, Pakistan, over 1,200 people died within days. In response, local authorities ordered mass graves to be dug in advance.[4] Extreme climate events such as these demand immediate spatial responses to mass death, rendering architecture reactive and ad hoc.[5]

These urgent improvisations expose a broader disciplinary failure: we design for lifestyles, not lifecycles; for growth, not cessation; for consumption, not decomposition.[6] What if the architecture of death—across species, systems, and scales—became central to our discipline? Such a shift would entail creating spaces that reckon with loss, metabolize ruin, and engage the ethics of mourning and repair.[7] It would mean training architects to build, unbuild, witness, and design with an awareness of shared finitude and ecological justice.

Pedagogies that need to die

Architecture schools frequently tout resilience, adaptation, and ecological sensitivity. Yet, death—ecological, infrastructural, and corporeal—remains a marginal subject, often relegated to niche studios or speculative projects. This omission is not neutral. It reflects an enduring discomfort with mortality that undermines our ability to design responsibly for a world in collapse. If we accept that architecture shapes the conditions of life, then we must also accept that it shapes the conditions of death. As climate change accelerates and infrastructures fail, death is no longer an abstract endpoint but a daily reality shaped by policy, planning, and design[8] From heat-related fatalities in urban heat islands to displacement and loss of ancestral lands due to rising seas, the built environment participates in systems that determine who lives and who dies[9]. To ignore this is to abdicate ethical responsibility and to perpetuate pedagogies that are ill-equipped to face the challenges of both the present and future.[10]

➔ Architecture’s Afterlife: Breaking the Profession that is Breaking the Planet

Designing Death Architectures

The provocation is thus clear: death architecture—not only for humans but for all forms of life affected by anthropogenic climate change—must become a core concern in architectural education and professional discourse. This is not to indulge in necropolitics or dystopian fetishism, but to recognize the urgent ethical, spatial, and material demands of dying well, and of enabling dignified transitions in the post-Anthropocene. Whether in the form of climate-responsive burial grounds, interspecies memorials, decomposable structures, or anticipatory infrastructural systems, the spatialization of death must be foregrounded as a legitimate and necessary typology. By ignoring this imperative, we allow built environments to default into sites of unpreparedness—into unmarked graves, into heat-trapped interiors, into boil-in-the-bag mausoleums for the living and the dying alike.

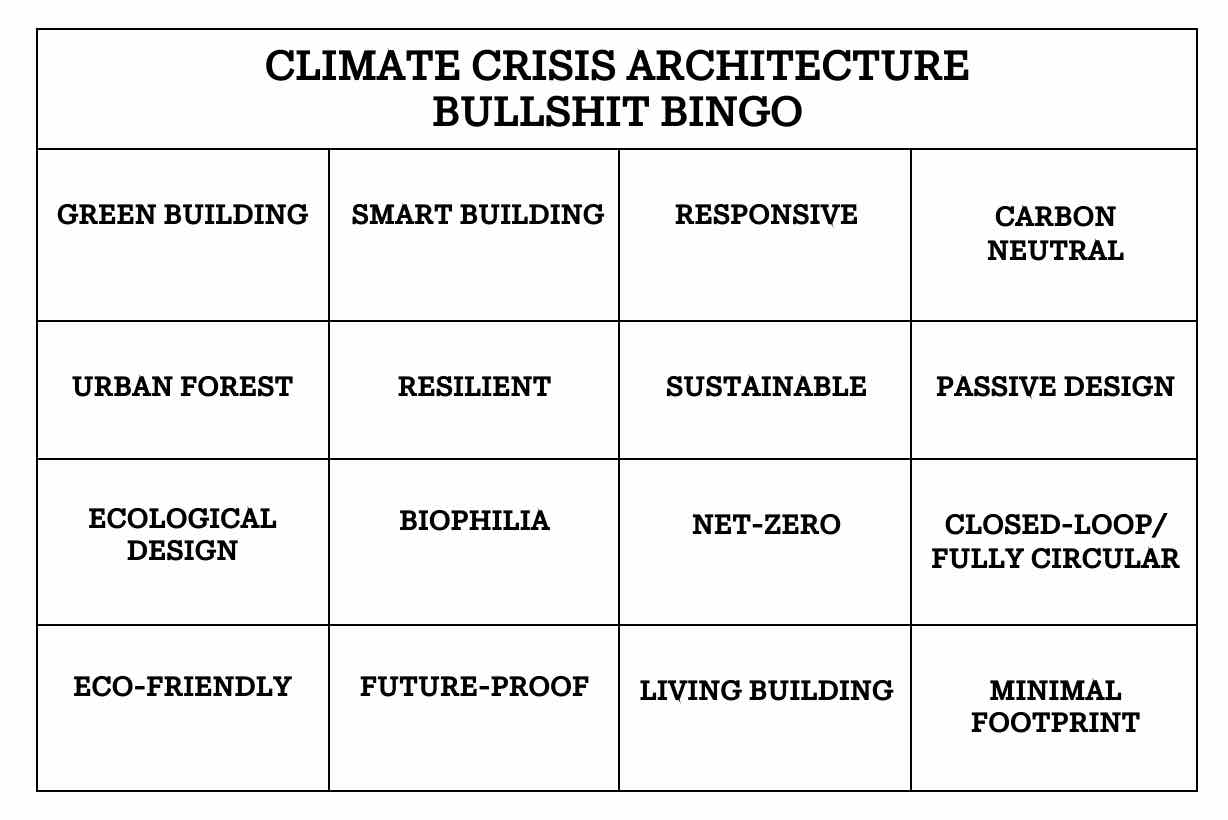

Climate Crisis Architecture Bullshit Bingo

One useful heuristic for evaluating whether the rhetoric surrounding climate-responsive architecture constitutes grounded speculation or unfounded certitude is to engage in a critical reading exercise—what might be playfully termed Climate Crisis Architecture Bullshit Bingo. The premise is simple: survey a range of leading architectural journals or attend an end-of-year design review at a school of architecture, and note the recurrence of familiar tropes—’net-zero,’ ‘resilience,’ ‘regenerative design’—deployed often without rigorous substantiation. While visionary thinking is a hallmark of architectural discourse, the concern here is not with ambition per se, but with a drift into what might be characterized as magical thinking—a belief in the feasibility of ecologically sustainable design that disregards empirical constraints and systemic inertia[11].

As Climate Crisis Architecture Bullshit Bingo seeks to illustrate it is impossible to claim that a building can have zero impact on the environment over its entire life cycle. For example, embodied carbon in materials (concrete, steel, glass) is extremely difficult to offset, and renewable energy systems (like photovoltaics) rely upon ecologically harmful extractive geographies and involve significant carbon and footprints in their production. Moreover, ‘net-zero’ calculations often omit the full lifecycle of construction, maintenance, demolition, and replacement.

Similarly, ‘Closed-Loop’ or ‘Fully Circular’ buildings—that generate no waste, nor use any ‘virgin’ material inputs fail to acknowledge that degradation over time requires inputs of new materials, and that recycling processes require energy and often degrade material quality. Full circularity, in essence, ignores entropy, wear, and social technological obsolescence. No architecture is responsive, smart, resilient, green, passive, biophilic, or sustainable enough to stop climate collapse. We could go on: dismantling each of these terms effortlessly, but that would only ruin the reader's role in the game. What the bullshit bingo card reveals is not the humor as much as the embarrassment of just how little we choose to understand, how misplaced our priorities are and precisely why we come across as arrogant, complacent, ill-formed and quite frankly, an ‘unreliable witness’ to a wider public on matters of climate collapse. Even an ‘urban forest ’is a misleading oxymoron since it dilutes the ecological meaning of forests, which are typically defined as vast, biodiverse, naturally carbon-positive and relatively undisturbed ecosystems.[12] Applying the term ‘urban forest’ to fragmented, diminutive and heavily managed green spaces demonstrates how susceptible architects are to greenwashing and obscures the urgent need to protect intact natural forests.[13]

Extractive Grief: Whiteness, Colonialism, and the Mass Death of More-Than-Human Worlds

Seldom discussed in architecture schools or practices are the reparative obligations we carry towards colonized, enslaved, and exploited human and non-human species for whom the impact of this trauma has never ended. As indigenous environmental philosopher Kyle Powys Whyte points out, ‘colonialism is a form of environmental injustice,’ stressing that Indigenous communities have long lived with the consequences of systems that exploit both human and more-than-human life for extractive gain. These are not abstract harms, he notes, but ‘cycles of unsustainability’ in which the loss of species, ecosystems, and ancestral relations constitutes a persistent space of mourning.[14] Such grief is not merely emotional—it is structural, ongoing, and geographically inscribed in clear-cut forests, toxified rivers, and collapsing habitats. These landscapes function as dispersed necropolises—sites of ecological death and memory. Echoing this, Naomi Klein identifies what she terms the ‘extractivist mindset’—a worldview in which land, labor, and life are viewed as inert resources to be mined for profit. ‘The extractive mentality that has so long governed [Western] relations with the Earth,’ she writes, ‘also governs relations among people’.[15]

Underpinning this mentality is whiteness, not just as identity but as a totalizing epistemology and technology of control—one that structures the colonial-capitalist matrix and renders mass extinction thinkable, even normal. The complicity of whiteness in ecological destruction is not reducible to individual actors but embedded in the architectures of power that define who and what is grievable. Judith Butler reminds us that mourning is always political: whose death counts, and whose doesn't, reflects the racialized calculus of value. When entire species are extinguished without ceremony, and biomes collapse without eulogy, we must ask: what forms of life have been rendered unworthy of grief under regimes of white extractivism?[16] Thus, confronting the climate crisis demands far more than technological innovation or policy reform. It requires a reckoning with the racial, colonial, and necropolitical foundations of environmental collapse. It demands that we inhabit and hold space for mourning—not only for human lives lost, but for the vast more-than-human worlds extinguished in the name of ‘progress.’

The Career Path No One Warned You About

Over several decades, decent and self-taught environmentalist architectural educators have worked in earnest to integrate the kinds of terminologies and frameworks that climate crisis architecture bullshit bingo critiqued into the curriculum with the best of intentions, and, with low to no support from the professional accreditation bodies whose conservatism has long limited substantive reform.[17] Yet despite these pedagogical efforts, the pace of ecological degradation—marked by intensifying climate data and cascading environmental thresholds—has outstripped the rate at which curricular and professional transformation has occurred.[18] [19] The problem is not only that the stated environmental goals of architectural proposals remain technologically or politically improbable; it's that the opportunity to achieve them may already have passed. In this context, the persistence of utopian design narratives risks obsolescence, not inspiration.

But as the climate crisis accelerates, in response, architectural education is beginning to confront a new paradigm: not only designing for resilience and refuge, but for disappearance and death. This emergent terrain, which we term death architecture, invites students to reimagine the built environment as a site of mourning, extinction, and managed collapse. Vocationally, this shift reflects a bitter irony. Architecture has historically aligned itself with the aesthetics of permanence, yet now must reckon with its obsolescence. In this context, architecture becomes less about building anew and more about managing decline, memorializing loss, and attending to what remains.

Dossier: Architecture and Activisme

By seeking to work with—rather than resist—the reality of multi-species decline, we might take on a more modest, restorative role in shaping a living rather than a dying post-Anthropocene. What is ending is not nature itself, which has always cycled through life, death, and renewal, but the extractive systems, especially capitalist expansion, that have brought us to this crisis. Architects, among others, can help give these systems the kind of funerals they deserve. This would allow new, humbler approaches to arise, grounded in interspecies collaboration and survival, attuned to the interdependent ecosystems on which all life depends. As neoliberalism fragments the profession and undermines its economic viability, increasing numbers of architects will find themselves paradoxically employed by climate catastrophe: designing fire-resistant shelters, flood memorials, and extinction archives. The way we will approach these tasks will be crucial. The following scenarios offer students and practicing architects some conceptual and practical tools to engage with these overlapping crises.

1. Climate-Adaptive Cemeteries: Designing for Impermanence

As climate change accelerates, traditional burial grounds are becoming increasingly unsustainable, particularly in regions affected by sea-level rise, coastal erosion, and permafrost thaw. These environmental transformations challenge both the physical stability and the cultural continuity of funerary landscapes. In response, the design of climate-adaptive cemeteries must embrace impermanence as a core principle, prioritising flexibility, transience, and ecological integration over permanence and enclosure. Future cemeteries may take the form of biodegradable burial pods within wetland ecosystems, floating memorial gardens that adapt to tidal shifts, or ephemeral digital-physical hybrids that archive memory while allowing the land to regenerate. These interventions must reconcile dynamic hydrological systems with situated mourning practices, creating responsive infrastructures that honour the dead while adapting to planetary instability. By integrating environmental forecasting, culturally attuned design strategies, and regenerative land practices, climate-adaptive cemeteries can offer a new paradigm for remembrance that is at once respectful, resilient, and impermanent.

2. Extinction Archives: Preserving What Is Vanishing

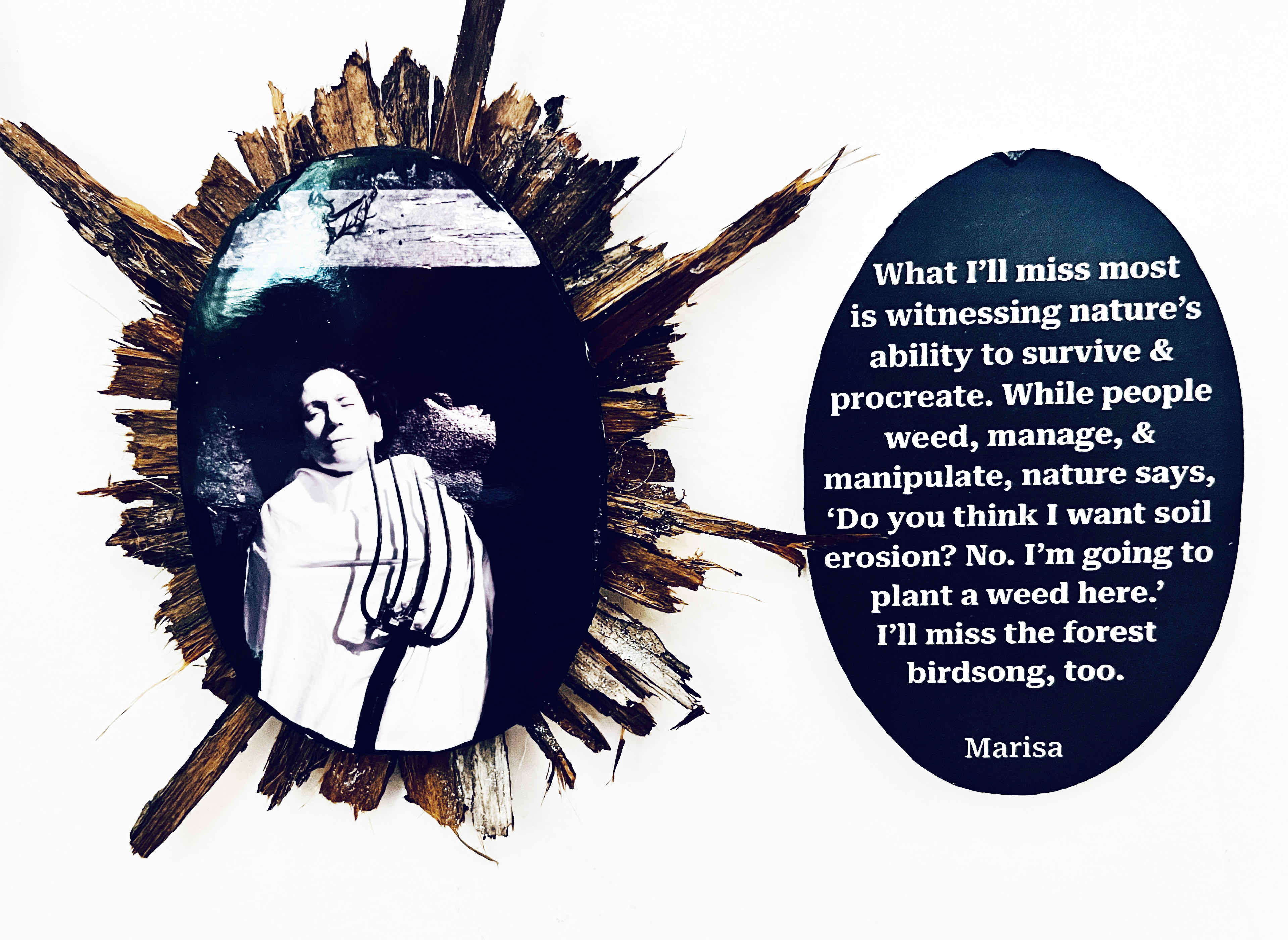

Extinction Archives are a gesture towards memory in a world where witnesses have vanished, a fragile offering to the future, even if those who access them are non-human forms of life. These archives—replete with samples of species, traditions, and languages—unlike conventional repositories premised on permanence—embrace impermanence as both a condition and an ethic. Each endangered entity—be it a collapsing coral reef ecosystem, the last spoken remnants of a dialect, or an ice-dependent festival tradition—is treated as a unique client requiring a bespoke spatial, material, and symbolic response. For example, an archive for a disappearing bee species might consist of biodegradable pollen vaults embedded in rewilding landscapes, while one preserving glacial knowledge could take the form of melt-responsive installations that decay in synchrony with the ice they commemorate. Such designs refuse the illusion of durability; instead, they foreground ephemerality, decay, and the temporality of grief. Preceding a potential collapse of human existence, the interim utility of these archives as public spaces invites students to confront the ethics of memory-making under conditions of planetary loss—not to immortalize, but to witness, to hold space, and to let go. These archives, then, are not static vaults but performative spaces of urgency, ritual, and vanishing.

3. The Shroud and the Shelter: Dual-Program Typologies

Where new structures are absolutely necessary, they should be conceived as dual-purpose architectures—designed not only for present use but for future obsolescence. These buildings perform a kind of anticipatory grief, embodying the knowledge of their own eventual abandonment or transformation. A wildfire shelter, for instance, might later serve as a site of remembrance; a flood-resilient community center could be prefigured to dissolve into an ecological ruin. Some may even evoke non-lethal live burials—structures we enter knowing they may one day be sealed, submerged, or overtaken. These architectures must integrate material strategies for dignified decline: decomposable skins, biodegradable frames, or habitats that invite non-human co-inhabitants. Here, temporality is not a design failure, but a fundamental feature—an act of mourning made manifest in form.

4. Vocational Ironies: The Architect as Climate Undertaker

Confronting the professional implications of death amid climate collapse demands a deliberate resistance to the commodification of crisis. As the design industry begins to absorb climate-induced deathscapes—temporary shelters for the dying, mobile memorials for displaced communities, or ephemeral infrastructure for mass burials—architects must cultivate a critical awareness of the contradictions embedded in ‘designing for collapse.’ The profession risks becoming complicit in aestheticizing ruin unless it reckons with the ethical stakes of impermanence: designing not for permanence or profit, but for transience, mourning, and care. Commissions born of climate catastrophe must be interrogated not simply for their formal or technical merit, but for whom and what they serve—are they gestures of remembrance or instruments of spectacle? In post-neoliberal labor imaginaries, where the creative mandate is no longer yoked to growth imperatives or extractive economies, architects can begin to construct modes of practice grounded in solidarity, refusal, and temporal humility. Here, impermanence becomes a generative ethic—an architecture of holding space without possessing it, of making without permanence, of grieving without capitalizing on loss.

A Eulogy for Architecture

Returning to the title of this article, it’s not only that architects are shifting from making shelter to shrouds, but that the architecture profession is contending with the shroud monumentalizing its own existential plight. In the most direct sense, the real ‘vocational irony’ invites us to mourn ourselves—a discipline and profession once rooted in shelter, community, and aspiration. A noble pursuit that lost its way, seduced by the illusion that specifying ‘sustainable’ materials and applying the latest green technologies could atone for its sins. As the Earth burned and waters rose, architecture kept building—still pouring carbon into the atmosphere, still serving systems it should have dismantled. It told itself it was helping. Architecture called billionaires' bunkers ‘progress’. Architecture called Martian colonies ‘hope’. Architecture called LED lights and exposed ductwork ‘salvation’. But what Architecture refused to do was stop. Perhaps its greatest possible act of resistance would have been abstention: to put down the pencil, to withdraw its labor, to say or do no more. Instead, it clung to a failing paradigm of growth, masking complicity with the language of sustainability and resilience. In the end, it mistook complexity for wisdom and action for meaning. It forgot that to design well, one must first listen—to the land, to the people, to the silence after collapse.

We say goodbye not to the idea of architecture, but to what it became: a mirror of techno-utopian delusion, a scaffold of late-capitalist guilt, a force too often aligned with destruction. May what comes next be quieter, humbler, and rooted in care. May we learn, at last, to build less—and to see more.

If you could see your whole life from start to finish, would you change things? Dr. Louise Banks[20]

Notes

- David Gissen, Subnature: Architecture’s Other Environments (New York: Princeton Architectural Press, 2009); SEE ALSO Brian Dillon, Essayism: On Form, Feeling, and Nonfiction (New York: New York Review Books, 2017).

- Petra Hönnighausen, Architecture and Death: On the Aesthetic, Spatial and Political Dimensions of Endings, (Berlin: Transcript Verlag, 2020).

- "The Architecture Salary Poll 2023" Archinect, 2023. https://salaries.archinect.com/; American Institute of Architects (AIA). Compensation Report, 2023. https://www.aia.org/resources/6153083-compensation-report-2023

- ‘Pakistan Deadly Heatwave’. Reuters, (June 26, 2015).

- Shazia Hasan, ‘Extreme Heat and Urban Deaths in Pakistan.’ Dawn (September 9, 2022).

- Peg Rawes, Architectural Ecologies: Politics and Ethics in a Posthuman Era (2013).

- Eyal Weizman, Forensic Architecture: Violence at the Threshold of Detectability (New York: Zone Books, 2017).

- Eric Klinenberg, Heat Wave: A Social Autopsy of Disaster in Chicago (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2002).

- Kyle Powys Whyte, ‘Indigenous Climate Change Studies: Indigenizing Futures, Decolonizing the Anthropocene.’ English Language Notes, 55 (2017): 153-162

- Amitav Ghosh,The Great Derangement: Climate Change and the Unthinkable (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2016).

- Simon Guy and Graham Farmer, ‘Reinterpreting Sustainable Architecture: The Place of Technology,’ Journal of Architectural Education 54-3 (2001): 140-148.

- Konijnendijk, C. C., Nilsson, K., Randrup, T. B., & Schipperijn, J. (2006). Urban forests and trees: A reference book. Springer.

- Heynen, N., Kaika, M., & Swyngedouw, E. (2006). In the nature of cities: Urban political ecology and the politics of urban metabolism. Routledge.

- Kyle Powys Whyte, ‘Indigenous Science (Fiction) for the Anthropocene: Ancestral Dystopias and Fantasies of Climate Change Crises.’ Environment and Planning E: Nature and Space 1-1-2 (2018): 224-242.

- Naomi Klein, This Changes Everything: Capitalism vs. the Climate. New York: Simon & Schuster, p.181

- Judith Butler, Precarious Life: The Powers of Mourning and Violence (London: Verso, 2004).

- Jeremy Till, Architecture Depends (Chicago: MIT Press, 2009).

- Will Steffen, Johan Rockström, Katherine Richardson, et al. ‘Trajectories of the Earth System in the Anthropocene.’, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 115-33 (2018): 8252–8259.

- IPCC, Sixth Assessment Report. Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (2023).

- The ‘fictional’ main character in the 2016 film ‘Arrival’, Directed by Denis Villeneuve and written by Eric Heisserer.

About the authors

Dr. Harriet Harriss (ARB, RIBA, (Assoc.) AIA, PFHEA, Ph.D) is a tenured professor at Pratt School of Architecture, where she served as the Dean from 2019-2022. An award-winning educator, writer, and UK-qualified architect, Dr. Harriss has established a global reputation for her books and publications that position social justice and ecological justice as pedagogic and professional imperatives. A Clore Fellow and British School in Rome Academician, Dr. Harriss’ most recent awards include an IPA (Institute of Public Architecture) Writer in Residence (Summer 2024) and an Arctic Circle Residency (Spring 2024). harriet-harriss.com

Roberta Marcaccio is a research and communication consultant, an editor, and an educator whose work focuses on alternative forms of design practice and pedagogy. Her publications include the forthcoming ‘The Hero of Doubt’ (MIT Press, January 2025) and ‘The Business of Research’ (AD, Wiley, 2019). Roberta is a Graham Foundation grantee and has been awarded a Built Environment Research Fellowship by the Royal Commission for the Exhibition of 1851 and a Research Publication Fellowship by the AA. www.marcaccio.info

![Proposal to repurpose one of NYC’s many glass towers - responsible for the deaths of approximately 250,000 migratory birds each year[[1]] - into a space for pollinator species archiving and collective grieving within nest and feather-formed structures.[1] Source: https://nycbirdalliance.org/our-work/conservation/project-safe-flight, Last accessed 2025-05-21 Harriss-Marcaccio-FIG.04](https://espazium.s3.eu-central-1.amazonaws.com/files/2025-06/Harriss-Marcaccio-FIG.04-pollinator%20archive%20and%20memorial-EN.jpeg)