What if…the Swiss pavilion had been designed by Lisbeth Sachs?

Interview with the five curators of the Swiss pavilion at the Venice Architecture Biennale

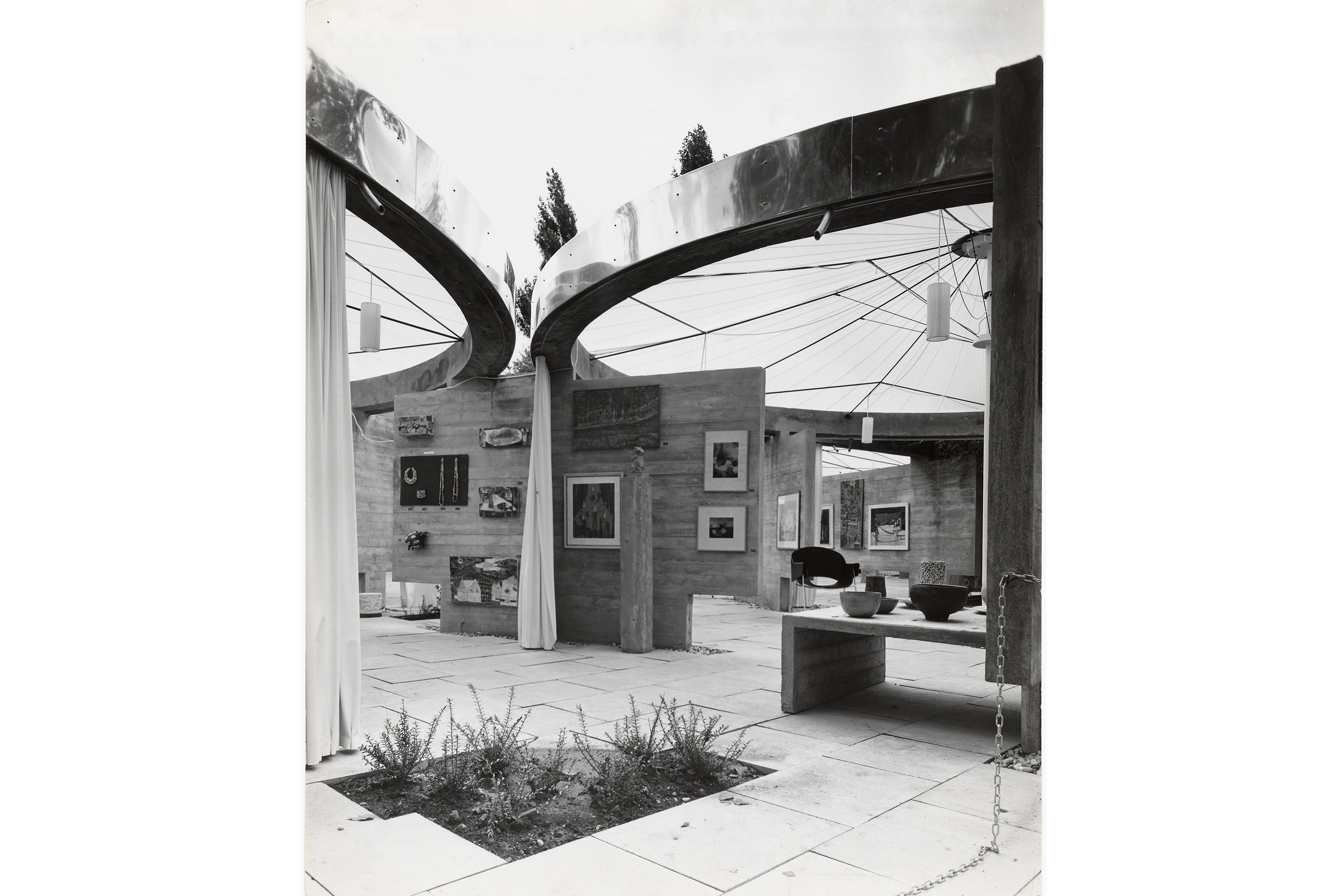

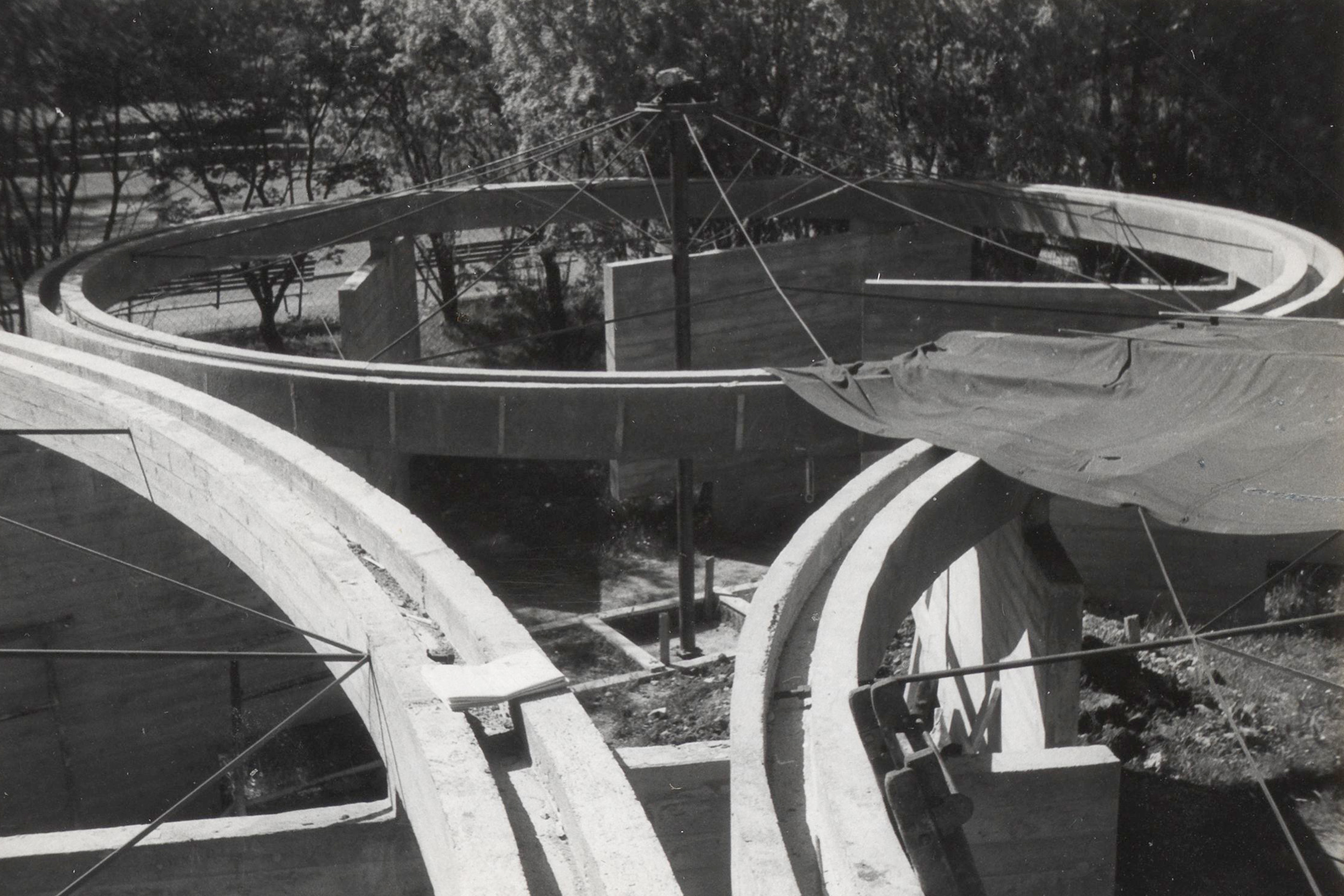

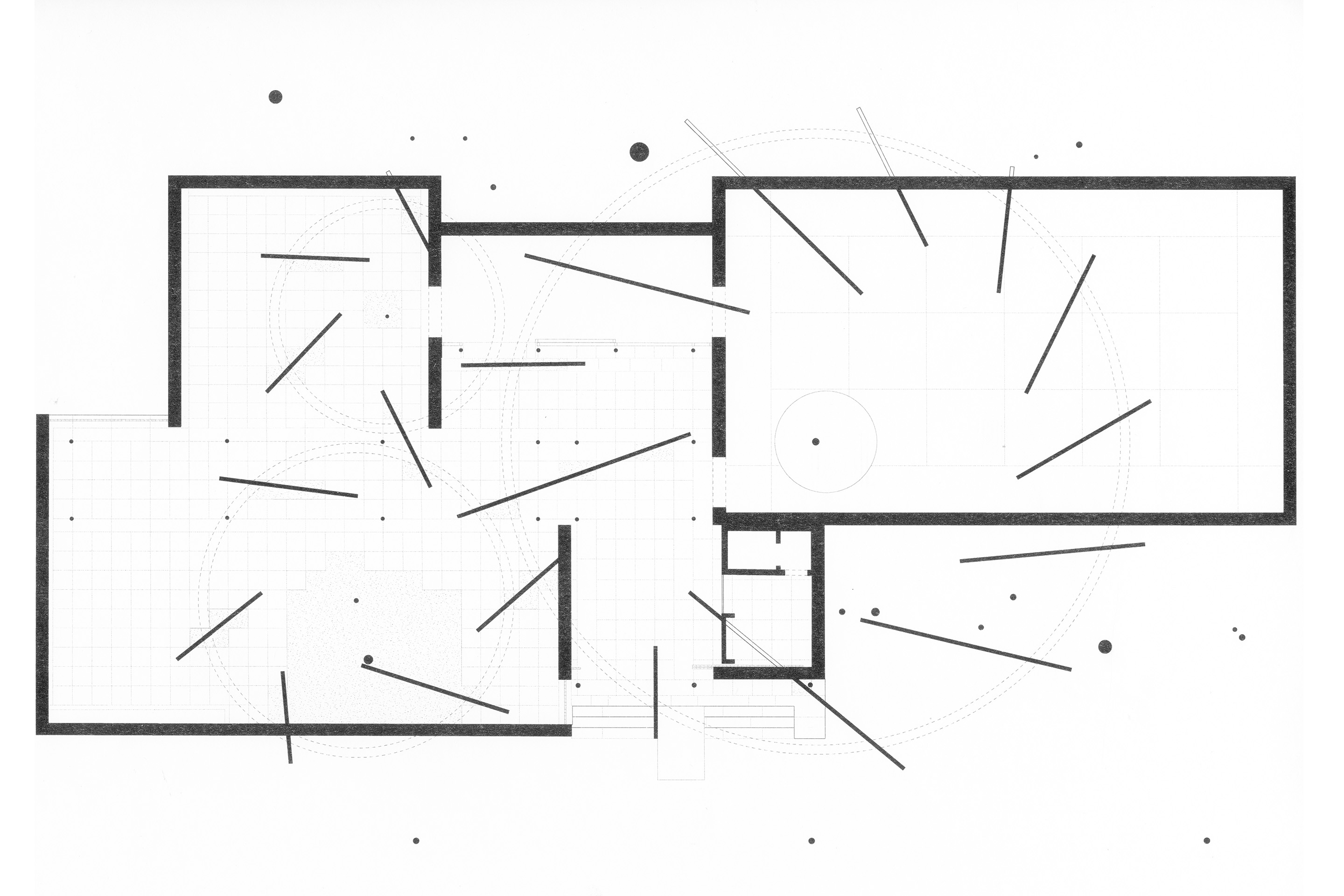

To give substance to a reflection on the lack of representation of women in architecture, the curators of the Swiss Pavilion are giving new life to the project of one of the first women architects registered in Switzerland, Lisbeth Sachs (1914-2002). In a subtle game of confrontation, the team reproduced fragments of an ephemeral art gallery (Kunsthalle) that she had designed in 1958 for the Swiss Exhibition of Women's Work (SAFFA) on and inside the rooms of Bruno Giacometti's pavilion.

Who was Lisbeth Sachs and why is her story so important to you?

Kathrin Füglister: As one of Switzerland's first female architects to establish an independent practice, Lisbeth Sachs was a pioneer. Her approach in architecture was very respectful and inclusive towards all available resources, from labour to nature in general: she understood herself as a bridge-builder between the environmental conditions and the diverse people involved, rather than as a specialist.

Your proposal for the Venice Biennale involves literally superimposing fragments of the Kunsthalle—a short-lived art hall designed by Lisbeth Sachs for the 1958 Swiss Exhibition for Women’s Work (SAFFA)—onto Bruno Giacometti’s Swiss Pavilion (early 1950s). What are you looking for, a comparison or a confrontation?

Amy Perkins: Neither: We call it an overlay or a superimposition, but really it’s a translation. We stay true to the original dimensions of Lisbeth Sachs’ pavilion but mirror it, like an imprint. The moments where the two pavilions meet, a new kind of space is produced. It’s less a confrontation than a speculative dialogue, asking: What if? – what if it had been otherwise? What if the Swiss Pavilion had embodied another architectural gesture entirely?

Elena Chiavi: to give a translation of the Kunsthalle (which no longer exists), we drew inspiration from visiting Sachs’ surviving built works such as the Haus am Hallwilersee or Baden’s Kurtheater, the latter recently undergoing meticulous renovation by Elisabeth and Martin Boesch.

‘Endgültige Form wird von der Architektin am Bau bestimmt.’ - “The final form will be determined by the architect on site”: what a strange title for an installation! Is it an archive document or a manifesto?

Kathrin Füglister: In the gta Archive, where Lisbeth Sachs’ archive is held, we uncovered this sentence as a handwritten annotation on a 1:20 drawing—a very unusual detail within the 1950s profession. We understand it as a bold declaration of autonomy, affirming Sachs’ leading role both on the construction site but also in the project’s conceptual development.

Myriam Uzor: As an architect you normally seek for a final form. We try to decide on site, we leave the project partly unfinished and open, flexible and adaptable. This needs constant dialogue, not only between the two architectures but also within our team and with the many actors coming from different fields.

Axelle Stiefel: The German word bestimmen (to decide) refers to Stimme, the voice. Wer bestimmt was – who decides? The site ? It can have a voice too, eine Stimme. It’s all about finding the right Stimmung, when everything is stimmig, falls right. There are many voices in there, whether human or not. And also the voice of the architect, Lisbeth Sachs. Or perhaps her ghost, still present.

This collaborative and open process is central to your approach. Instead of giving instructions from a distance, you work on site in Venice, together, and in direct contact with the site workers. Why is it so important to your approach to proceed in this way?

Elena Chiavi: For this collective building process, we prioritize connecting with all the specialists and workers rather than imposing our vision. However, we work in a field that is still run by men, and we are in contact mainly with male partners on site. Even if everything progresses smoothly, at different occasions during the process, we have felt vulnerable. To achieve this collaborative work on site, we not only need to be heard but truly listened to.

Axelle Stiefel: Stepping onto the 7am vaporetto to the Giardini, we’re acutely aware of our visibility (since almost all the passengers on board are men). That exposure lingers on-site, where decisions we’ve made as architects or artists are suddenly up for debate by those who assume authority over our expertise. The Annexe group’s practice doesn’t just amplify women’s voices; it makes systemic vulnerability legible—then reflects it back.

Axelle, as an ‘embedded artist’, you accompanied and recorded the four members of the Annexe group throughout this process. How important is the sound dimension in the installation?

Axelle Stiefel: The installation invites you to listen through the architects’ ears and take awareness of the soundscape. The four members of Annexe have been provided with a recording device each, without any instructions, capturing field recordings during a residency on the Furka Pass, as well as walks or gatherings in Lausanne, Zurich, Geneva, London, and Venice. During continuous listening sessions, we revisited these recordings together, extracting design principles that would later be applied to composing the sound installation for the pavilion. The collection is a testimonial to that time, to the whole process of building.

You point out that no pavilion in the Giardini of Venice was designed by a woman. Is this one of the reasons that led you to make this proposal?

Amy Perkins: Very early on, we came to the realisation that the Giardini is essentially a "no-woman's land." It was a trigger that led us to search the archives and find an equally strong female figure to Giacometti, the architect of the Swiss pavilion. Although this is now changing, whilst I was studying I was rarely shown examples of great pieces of architecture designed by women. We all have experience in teaching and know that the most powerful thing for students is to experience space itself. This is why we wanted so badly to rebuild this unique pavilion, even as a translation.

Myriam Uzor: References don’t come from nowhere. In our way, we hope this platform can help surface voices that deserve more attention.

Is rebuilding this pavilion a way of giving Lisbeth Sachs her place in the history of architecture, a kind of reparation in short?

Amy Perkins: You can’t “repair” history, but you can shift the conditions that once prevented it from finding its place. Translation is always an act of adding yourself to an existing work.

Myriam Uzor: In our proposal, Lisbeth Sachs Kunsthalle exists not only in history but also in the present. And it becomes a new architecture — not a reconstruction of her work, but an interpretation. Of course, since Giacometti’s pavilion is standing there, the space you experience will be entirely unique, something entirely new. We’re not doing an exhibition about architecture—we’re making architecture.

Would you say that if women had been better valued and represented in architecture until now, other themes, other processes, or even other types of public spaces might have emerged?

Kathrin Füglister: Diversity in a broader sense is key. It is not only a question of gender. In any situation, collaboration or field, it’s the diversity that makes it possible to come to some solution, or some conditions that are good to the broader audience. What the project does is acting in the now. We cannot answer in the past.

Axelle Stiefel: We’ve already changed, this movement began long before us. Annexe's response is to discuss models – modes of working and find points of contact in history through the work of women, which is crucial to providing a longer perspective. So, acknowledging that you’re already changed in the present is important, to be able to say "Yes, we will support change by fostering the conditions needed to sustain diverse voices." This is how we participate in building a more sustainable future.

How do you do this?

Elena Chiavi: We take a lot of time to exchange, discuss, and understand where we stand. We are not trying to be the most efficient or aim for a specific result. We are engaged in a movement of figuring out how to work together, questioning the processes, the system we are in, and how we build today.

Myriam Uzor: We can’t change the past, so the right question is “where do we stand now?”. Through this contribution for the Swiss pavilion, we make an experimental proposal that hopefully triggers another step, and another one. And this is where fiction comes in again, as a very productive tool of imagination: “What if… ?”

EXHIBITION

10.05–23.11.2025

Endgültige Form wird von der Architektin am Bau bestimmt

Swiss Pavillon

19th International Architecture Exhibition

Biennale Architettura 2025

Venice